Geologist, educator, author, and artist

I’m working on a book about how different people see the Earth.

Here’s what I’m thinking…

The Earth talks to us. What do we do with all that information?

I’ve dealt with data my entire life—mineralogical, test scores, demographics—along with all the things we do to data—label, digitize, visualize, archive. We literally have so much data we hardly know what to do with it.

more

We scientists live immersed in data. It’s what most of us do – gather it, interpret it, and report on what we find. Where does the data come from and what does it tell us?

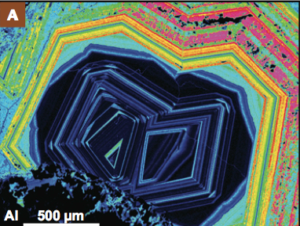

Think about all the data we can get from a single mineral grain. A rock might sit around for billions of years – or millions – or tens of thousands. It weathers and falls apart and the grains get washed down the hill, into a stream perhaps and bounces along the bottom or gets caught up in a swollen river. Eventually the rains stop or the stream runs into a still pool of water and more sediments cover this little grain, burying it beneath thick piles of sediment. It becomes a rock over time, and in another billions or millions or tens of thousands of years later, a geologist comes along, picks it up and describes it. She writes down her observations of where she got it, what does the outcrop look like, what day it was – hence, starting the data collection. Where was it sitting, what does it look like, how does it relate to the other rocks in the area?

She takes it back to the laboratory, crushes it, perhaps measures its chemistry, and take more data. She finds some interesting minerals and plucks them from the crushed rock, puts them on a slide and into a machine that measure its chemistry or perhaps its isotopes, telling her how old that grain is. These data are the ties that link the person today to what happened in the past, possibly billions of years ago.

If she is clever and perseverant, she writes a paper about that grain (and perhaps its friends) and it gets published in a journal. Some librarian takes the data from the journal and puts it into a catalogue. If her organization has a museum, she might deposit the grain in its collection and the museum curator would put more data about the grain into their data base. Who uses it, where the grain is stored….on and on it goes.

How else do we look at data? We have student data – their courses, grades, where they live. We have data on the people who live now and move across the planet. We have data on the diversity of plants and animals – although this group of data are very incomplete. How little data we have on the diversity of life on this planet– even as we as humans are decreasing that diversity.

I have spent my life dealing with data: geochemical, mineralogical, geodetic, test scores, student grades, demographics, and more. There are also all the things we do to data and for data: write, label, store, digitize, spend money, categorize, visualize, archive…on and on it goes.

And how do we access this data? I learned about data products when I worked in an organization whose main function was to acquire and store geodetic data. First order data was that which came straight off the machine – the instrument designed to collect it. It was one person’s job – his life work to turn that into second order data – numbers that could be then used by techies and scientists. Third was something more easily determined by a variety of people who might want to use it – in this case, time series of earths movement. And in the education business, we wanted to turn the data into fourth order data – visual or easily accessible by a wide range of audiences including you and me.

Some data is inaccessible to us from the very beginning – buried in the Earth, eroded, weathered, removed through anthropogenic means…and then when we interpret it as humans, the data can again be buried in archives, degraded, destroyed, or be inaccessible through lack of resources. Inequality exists even in our digital age.

Who has the access to the education needed to interpret all this data? Figuring out what the information of one little grain is hard enough. How do we figure out what terabytes of data tell us?

☒ Close

How do I answer the person who asks me “What does geology have to do with climate change?”

New Zealand Kaikoura peninsula with the Seaward Kaikoura Range in the background. The Hope fault is at the base of the mountains. Photo courtesy of T. Gardner, copyright 2015.

This question prompted considerable head-scratching on my part, for although I thought I knew the answer, it’s complicated. Simply, the use of water, minerals, and fossil fuels are strongly tied to people with their politics, economics, beliefs, and actions.

more

The person who asked this question is very smart and very well educated and a real activist on climate change. My first response was ‘Really?’ But then I had to think about this. Not everyone is a geoscientist and certain, we geoscience types don’t always know what is going on across the discipline.

Climate Change is one of the wicked problems. Wicked because of their complexity. Originally it was a policy definition, but I use the word and hear it bantered about among certain people – mainly in geological circles. Rittel and Webble first1 coined the word wicked and characterized a wicked problem by being unique to itself; lacking a definitive formula; no way to determine when a solution has been discovered; there may be better or worse solutions, are long term and can’t be tested, only implementation when trying to solve them, have many explanations, and no list of possible solutions.

And last, my favorite: those who try to solve them are held responsible for their actions. I hardly think in today’s world, anyone wants to be held accountable. Not the way of the early 21st century!

When I list the wicked problems of geoscience – and I almost write geology, for I am a geologist, I realize I need to make clear the difference in geoscience versus geology. Geoscience encompasses the entire earth system – the air, water, oceans, land, and even the geology of the planets. Generally, geology is about earth – the land and, of course, the water on and in the land masses. Atmospheric scientists are geoscientists who study the air – and its relationship with the water, and land. Oceanographers geology have to do with climate change – I would divvy up my response to show the main issues facing each of these subdisciplines of geoscience. And if I keep on listing – and drawing little lines between and among the topics – it gets so complicated – the relationships so dense – that I go away for a few minutes to clear my head from the wicked nature.

For more answers to this question, you will have to wait for my book.

☒ Close

Are we prepared for the new rush toward mineral exploitation for a green economy?

Sulfur miners in Ijen volcano, East Java, Indonesia. Shutterstock photo.

The current use of the word ‘harvest’ in place of ‘mining’ on the deep sea floor is another sugar-coating or perhaps green-washing for a process that is difficult and dirty at best. At its worst, mining devastates people, their communities, and the environment.

more

My colleague walked into my office and said “I’m engaged.” “Wow” I replied, “I’m so happy for you.” After the celebratory hugs and laughter, she said, “I want to have a ring of sustainably harvested platinum.” I’m sorry to say that I couldn’t help but laugh.

“Platinum is mined,” I said. “Mining is not sustainable – we use up what comes out of mines, and, eventually, it will all be used up. Maybe you mean recycled platinum. Where on earth did you hear about sustainably harvested platinum?”. To me, it was a public relations ploy by a jewelry company.

I’ve learned more about mining and sustainability and recycled precious metals in the past decade. I still don’t know what sustainable means to most people – it is a wonderful catchword bantered about that can cover everything from eating fish to the new green energy-craze. And I certainly don’t understand why I see the word ‘harvest’ in place of mining today. I think it is another sugar-coating for a process that is difficult and dirty at best. At its worst, mining is devastating to people, their communities, and the environment.

I had forgotten this engagement ring until recently reading an article on deep-sea mining for the metals we think we need to increase green energy to move rapidly away from a fossil-fuel economy. This was an excellent, well-written, and highly researched article on the state of exploration for mining the sea floor. The mining companies want to know how to do it, and marine biologists, climate scientists, and environmental advocates want to know how this will impact the biota that live on the sea floor, how sediments will circulate and affect ocean temperature and currents that drive the global weather patterns, and how the mining itself will affect communities near the sites as well as who process mega-tonnage of materials to extract the targeted metals. We know so little.

But I was disturbed, very disturbed, to read in the article’s subtitle that the mining of the ocean’s floor was called ‘harvesting’ and that the mining would ‘pluck’ the nodules to bring to the surface. In my experience, the word ‘harvest’ applies to things we grow as crops. We normally don’t harvest native forests, but it is fair to say we harvest trees from plantations in which trees were planted with the purpose of cutting them down for our use. We think of autumn as the harvest season when we reap the benefits of nature’s and agriculture’s bounty – wheat, apples, squash, tomatoes, corn – a whole host of yummy food. We don’t use the word harvest indiscriminately, however. We ‘gather eggs’, ‘make hay’, ‘milk the cows’.

We don’t harvest coal from the mountains of Kentucky and West Virginia. We ‘strip mine’ – blasting and bulldozing the tops off mountains to recover the thin layers of coal. We push that mountain top into the valleys and streams – and most of the time, coal companies don’t reclaim the land like they say they will. This, in no way, resembles a harvest or plucking of coal.

As for the word pluck, I might daintily pluck a dead rose from the bush or pluck a grape from a cluster on a charcuterie board. I pluck my eyebrows – quickly wrenching each hair out by its roots to minimize the pain. A more vivid and less bucolic plucking of chicken feathers takes place in enormous meat-packing factories across the world. That is not dainty but hot, dirty, and dangerous. We just don’t see it everyday.

And we won’t see the dredging of the sea floor – scraping sediments up in vast quantities, stirring up the mud, and killing whatever life there is in the mined area. We don’t even know what the life is. We don’t know how the sediments will affect the movement of currents or the stratified temperature zones. We don’t know how much sediment will be moved to recover parts per million of the metals.

We don’t know how messing with our ocean environment will affect our planet . Maybe even worse than using fossil-fuels? We just don’t know.

☒ Close

How do the Earth, the planet, and the world intersect?

Geological map of central Kentucky, Kentucky Geological Survey.

I thought I was writing about the Earth when, in fact, I am writing about how a person constructs a world view. While writing about how other people might see the Earth, I’ve learned a lot about myself.

more

The Earth has a mass of 5.972 × 10 24 kg and moves around the Sun at a speed of 30,000 meters per second. The temperature at its center is around 5,200o Celsius.

Earth is a thing with these qualities. I’ve never particularly cared about the planets, but one night I sat at the dinner table with a man who studies the wobble of the Earth. I asked what exactly he does to study that phenomenon – he analyses many GPS sites to find a solution for the entire planet. A solution, in this context is a formula that all the data fit. He loooks at the whole in order to solve his problem – which is not the exclusive purview of nerdy geophysicists but is also our problem, that of the everyday ’Joe’. Our use of navigation systems depends on knowing where the satellites are in relation to spots on the earth. Hence, we have to know how much and in what direction we are wobbling at any moment.

I feel a bit of affection for a planet that wobbles. The fact that it makes smile means a wobbling Earth is part of my world view.

☒ Close

How to Be A JEDI in 2026?

Artisan amethyst miners, Mapatiza, Kalomo,Zambia, photo by Daniel Munalula, courtesy of Patricia Ongwe Zita.

Broadening participation in geoscience has rightfully evolved into BElonging, Accessibility, Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. In the meantime, geoscience has grown into a community that no longer relies primarily on white people to advocate for these principles. Where do I put my energies now? Natural resource justice for women and children in mining? Continued mentoring of geoscience students?

more

Geoscience persists as having one of the lowest percentages of underrepresented minorities as students and as professionals. I sat as the only white person in a room at Virginia Tech to tell them about a new project to increase representation in the sciences. The members of the Black faculty organization asked me why I was there – and didn’t buy the argument that there was only one African American geoscientist in a university in Virginia. I still think that was true.

Today, we are populating the diversity committees and the leadership positions with and that’s ok.

I am at the end of a career in geoscience so I’m more interested in hanging out with those who are thinking about ethical sourcing of gems and metals and about the working conditions of women and children in artisan mines – maybe it is white-centered to think I can help.

I started on this journey with using the beautiful stone beads I had accumulated over 20 years of attending gem and mineral shows. As I learned more about the business of gemstones, I migrated from wanting simply – and it really is not simple – to know where my rocks came from to wanting to ensure that the people who touch these stones along their journey have a living wage, safe working conditions, access to school, and some environmental safeguards. Not an easy task in the jewelry industry – or, as we know from frequent news stories – for many of our modern products that we take for granted!

I am a failed entrepreneur—I get a grade of 2 out of 10 on Harvard’s quiz. But I love gemstones and jewelry, and I like the people in the jewelry industry who are working toward a transparent and ethical trade. And I still think we need to know where our rocks come from!

☒ Close

How do we escape our silos?

Dunite nodules in basalt, western Victoria, Australia. Photo by S. Eriksson.

“Don’t talk about that” or “Who are you to write about that?” Scientists don’t really want to talk to social scientists, let alone artists. How do we get ‘all hands on deck’ to generate innovative solutions for the world’s pressing problems?

more

A very few years ago, the director of the organization where I worked said, “We need to be more interdisciplinary in our research. Let’s do something with geophysics and geology.” I metaphorically rolled my eyes. (I do that a lot.) The scientific world had moved beyond that, so why didn’t he know?

Once upon a time, I was told by a colleague not to say the word theology in the science building. I’ve been told that metaphors in science are trivial. Some people – a lot of people, stay in their lanes and want to keep everyone else there too.

There is a certain gemstone, an alexandrite – if you turn it one way it is lavender – from another angle it looks pink. And then there is the Victorian poem, turned into a song, about the men of Hindustan who each approach an elephant, not being able to see the entire animal. Politically incorrect today but very accurate in how we make assumptions based on our limited knowledge, I might rewrite the song with a different outcome when the men get together to compare what each one knows. Oh, another verse might do it.

Fortunately, or not, I have many interests and enjoy making the links between and among disparate topics. I am literally a jack-of-all traces – rather a jill-of-all trades – not the master or mistress of one.

☒ Close